Table of Contents

- 1 The Australian Dairy Industry: The Life of the Dairy Cow

Voiceless‘ latest in-depth report, The Life of the Dairy Cow, offers valuable insights into the emotional stress and physical strain experienced by the modern Australian dairy cow.

Watch the follow-up discussion panel video “Rethinking Dairy Cows“.

Through rigorous analysis of current scientific knowledge as well as the examination of the relevant legal framework, this report highlights the need for change in the way these emotionally complex animals are treated. The report has been reviewed by five leading animal welfare experts from Voiceless’ Scientific Expert Advisory Council

The dairy industry has become one of the most egregious abusers of animal welfare among all of agriculture. All of these abuses are well chronicled in the Voiceless dairy cattle document, a far better document on dairy cattle welfare than I have ever seen in the US.

– Professor Bernard E. Rollin, Professor of Animal Sciences, Colorado State University.

Voiceless are an Australian community of internationally recognised individuals from the highest levels of science, law, business and the arts who are passionate animal advocates, dedicated to raising awareness of the plight of animals and to alleviating the suffering of animals in Australia.

Below is a summarised brief of the entire 82-page Voiceless report that has been prepared by Shellethics.

Background

Introduction

The first dairy cows arrived in Australia with the First Fleet in 1788. The seven cows and two bulls, like many of the early convicts, escaped soon after landing. After six years in the wild, the original nine had increased to a herd of 61.

Australian Dairy Industry in the 1900s.

Today, the Australian dairy producing herd is made up of 1.65 million domesticated cows and dairy is viewed as an integral component of Australian agriculture. Indeed, the significance of the dairy farm and the dairy cow have entered our consciousness through literature, art and more recently, marketing.

Marketing of dairy has been phenomenally successful. So much so that it seems to many that:

- Dairy is essential for good health;

- Cows need to be milked for their health and comfort;

- Dairy is essentially a ‘non-harm’ industry; and

- Dairy farmers struggle for a living and deserve public support.

The almost universal and unquestioned belief in the first three of the above points has enabled the Australian dairy industry to avoid much of the scrutiny that has been levelled against other animal industries. In short, they have flown under the radar.

Sentience

Sentience is the ability of a living being to perceive and feel things. Beings–human or animal–are sentient if they are capable of being aware of their surroundings, their relationship with other animals and humans and of sensations in their own bodies, including pain, hunger, heat or cold. A sentient animal is one who has interests, who prefers, desires or wants different things.

While most people now understand that animals feel pain, some find it more difficult to consider that animals are emotional beings who also seek pleasurable experiences. And again, there are people who can envisage these characteristics in their dog or cat, but who struggle to extend their empathy to farm or food animals who are often ‘seen’ to be less intellectually and emotionally complex. Recent research has provided evidence which shows that this is not the case.

A sentient being is a being who is subjectively aware; a being who has interests; that is, a being who prefers, desires, or wants.

Research shows that cows become excited when they solve a problem involving a food reward, cows like to be called by their name and then experience happier moods, cows also form close personal relationships with other cows and are negatively affected by long term separation.

The Five Freedoms

Nearly all discussions on the definition of ‘animal welfare’ will consider the Five Freedoms:

- Freedom from hunger and thirst;

- Freedom from discomfort;

- Freedom from pain, injury or disease;

- Freedom to express normal behaviour;

- Freedom from fear and distress.

Welfare Issues

Many of the welfare issues examined in this report can be attributed to the fact that the dairy cow has been genetically selected to produce such a huge volume of milk that her health and wellbeing are subsequently compromised.

Many of the welfare issues examined in this report can be attributed to the fact that the dairy cow has been genetically selected to produce such a huge volume of milk that her health and wellbeing are subsequently compromised.

Through selective breeding, nutrition and farm management, the modern dairy cow now produces more than twice as much milk as a typical dairy cow produced 50 years ago.

The process of lactation is hard work, yet dairy cows can be expected to produce milk at a high rate for ten full months of the year. These stressors have serious, sometimes disastrous, consequences for the individual cow.

High milk production quickly depletes minerals and nutrients, and it is not uncommon for cows to be undernourished and metabolically stressed due to inadequate feed, or an inability to digest the feed. This makes the dairy cow more susceptible to both viral and bacterial conditions, such as lameness and mastitis.

It is no wonder that while the average lifespan of a wild bovine is around 20 years, commercialdairy cows are generally sent to slaughter before they reach their seventh or eighth year, worn out and no longer producing enough milk to justify the cost of their feed.

Milk Myths

Australians have responded to positively to the clever marketing of dairy products. On average, we now consume around 107 litres of milk, 14kg of cheese and 4kg of butter per person per year, with the rate of consumption increasing annually.

However, the rhetoric surrounding mandatory dairy consumption is changing in Australia. For the first time in 2013, the Federal Government’s National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) included alternatives to dairy, such as soy, almond, rice and oat milk fortified with calcium, and endorsed a vegan diet

Now is the time for us to reconsider the huge quantities we consume each year and the potential for other non-dairy sources of calcium (fortified foods and vegetables) to fulfil our dietary needs.

Snapshot of the Australian Dairy Industry

The dairy industry is Australia’s third largest agricultural sector with a combined farm, manufacturing and export value of $13 billion in 2013. The national producing herd, which comprises some 1.65 million dairy cows, was expected to produced between 9.1 and 9.2 billion litres of milk in 2013/14, with industry projections for 2014/15 reaching as high as 9.4 billion litres

The dairy industry is Australia’s third largest agricultural sector with a combined farm, manufacturing and export value of $13 billion in 2013. The national producing herd, which comprises some 1.65 million dairy cows, was expected to produced between 9.1 and 9.2 billion litres of milk in 2013/14, with industry projections for 2014/15 reaching as high as 9.4 billion litres

Since the 1980s:

- Milk production has more than doubled,

- Individual cow numbers remained constant,

- Grazing areas have reduced by 35%,

- In the same time period, the average national herd size jumped from 85 to 220 cows per farm, with an increasing number of farms milking over 1,000 cows.

Essentially, Australian dairy farms are producing more milk using fewer cows and less space than ever before.

The Australian dairy industry is largely pasture-based, meaning cows are left to graze, however, it is now common for farmers to provide supplementary feeding with grains.

Producers supply milk and milk products both nationally and internationally, with Australia’s domestic market consuming 60% of all milk produced. The remainder is exported to overseas markets, mostly to Asia, which purchases 74% of all Australian exported milk products. Australia is the fourth largest exporter of dairy products in the world, accounting for 7% of the global export market, behind the EU, New Zealand and the US.

The average natural lifespan of a cow at good pasture, is around 20 years. Most cows used for dairy production, however, will never reach this age. The harsh reality of commercial dairying in Australia is that these cows are generally slaughtered before their seventh or eighth year. The main reasons for early slaughter are infertility, lameness and mastitis–diseases that are directly linked to the stresses of high production.

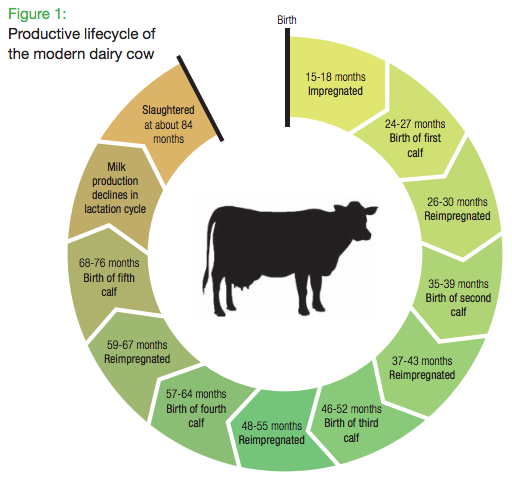

The modern day dairy cow’s short, exhaustive life.

During their short lives, a dairy heifer is typically artificially impregnated for the first time at between 15 and 18 months old. After a nine month gestation, she will begin producing milk after giving birth. For dairy farms maintaining a seasonal calving pattern with cows calving every 12 months, a cow will generally be re-impregnated two to three months after giving birth, meaning she will only have up to a 13 month reprieve between the birth of her calves.

A mother cow will continue to lactate and be milked during her next pregnancy until approximately 50-60 days before giving birth. This period is known as a ‘dry off’ or a cease milking period, and it allows for udder recovery, the treatment of mammary infections and preparation for birth.

‘Total Mixed Ration’ Feed

Dairy cows are grazing animals who naturally spend their lives on pasture where they can graze, forage and express their natural behaviours. Today, dairy cows who have been bred to produce huge volumes of milk may not be able to meet the extreme nutritional demands required to maximise milk production with pasture alone.

For this reason, some cows are fed ‘mixed ration’ diets, a high-energy blend of feedstuffs as partial of full supplement known as a ‘total mixed ration’ (TMR) system.

TMR dairy farms present a number of welfare issues for dairy cows.

It’s common for cows who are consuming large amounts of high energy feed to develop digestive issues like acidosis, which can cause anorexia and diarrhoea in cows and can lead to death if untreated. TMR systems also make grazing redundant, permitting dairy cows to be confined indoors for their whole lives and the Australian animal protection framework does not protect dairy cows or their calves from this.

While there are only a handful of TMR dairies in Australia, this type of intensive dairy farming should not be permitted to expand. This trend towards TMR is highly concerning, as it will potentially give rise to factory farm style mega-dairies, as seen in the US.

Antibiotics

In Australia, there is very little written about the issue of antibiotic use with farmed animals as there are really few industry resources to draw on.

Antibiotics are administered to dairy cows but typically the milk which is taken from them while they are on a course of antibiotics is not sold on to consumers. Accordingly, antibiotics are not typically used as a prophylactic but rather are administered on a therapeutic basis.

As the intensification of dairy farming looks to increase (i.e. TMR US style mega-dairies), the requirement for heavier antibiotic use will become apparent in order to fight diseases which develop inherently in factory farm intensive confinement environments.

More transparency is needed in this area.

Regulating the Welfare of Dairy Cows

The welfare of dairy cows is legislated by state and territory governments, with each enacting their own separate animal cruelty legislation and associated regulations. State and territory cruelty laws are generally focused on preventing gross acts of animal cruelty or neglect, while also providing certain minimum safeguards, such as requiring farmers to provide animals with adequate food and water.

Milk production has more than doubled as dairy cows are pushed beyond their natural limits.

Animal cruelty laws are presently complemented by the Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals – Cattle (2nd ed) 2004 (Cattle Code). The Cattle Code is not mandatory in any Australian jurisdiction, with the exception of South Australia, and compliance is voluntary

Victoria has its own Code of Accepted Farming Practice for the Welfare of Cattle 2001 (Victorian Cattle Code)

The draft Australian Animal Welfare Standards and Guidelines for Cattle (Version 1) is currently in its final stage of review, and will replace the existing Cattle Code to regulate the treatment of animals on dairy farms.

An absurd provision, which shows how little this report will improve the welfare of dairy cows in Australia, states:

“A person handling cattle must not … (3) strike, punch or kick, cattle in an unreasonable manner”

– Draft Cattle Standards and Guidelines S5.2(3).

When is it ever reasonable to strike, punch or kick a cow?

Legalised Cruelty

While the draft Cattle Standards and Guidelines will contain mandatory ‘standards’, most of the provisions relevant to dairy cows are expressed as mere ‘guidelines’. These guidelines are voluntary and unenforceable.

Further, many of the protections in the Cattle Code and the draft Cattle Standards and Guidelines are couched in highly subjective ‘welfare words’, such as ‘should’, ‘may’ or ‘reasonably’, effectively renderingthemlegally unenforceable

Most jurisdictions prohibit ‘unnecessary’, ‘unjustified’ or ‘unreasonable’ acts of cruelty. The law does not provide any guidance on what these ‘welfare words’ mean, but in practice, they operate to permit a number of otherwise cruel husbandry practices, such as tail docking, dehorning and disbudding, and calving induction.

Unfortunately, the draft Cattle Standards and Guidelines will do little to improve this situation, permitting:

- Dehorning and disbudding of dairy calves under the age of six months old, without pain relief;

- Chemical (or caustic) disbudding of calves less than 14 days old;

- The killingofone-day-old calves with a blow to the head with a blunt instrument; and

- Calving induction on the advice of a veterinarian, with no express prohibition on its use as a herd management tool or for non-therapeutic purposes.

There is an important distinction to be made between preventing acts of cruelty towards animals and ensuring their welfare. The animal cruelty legislative framework, in effect, operates to protect farmed animals from gross, intentional acts of cruelty or gross acts of neglect when they are detected. It is a sad reality that other considerations–such as the ability for animals to function well, to feel well, and to live out a natural life–are mostly unprotected by law, and are secondary to maintaining the commercial usefulness of these sentient beings.

Mother and Calf

Mother-Calf Separation

Like other mammals, a mother cow must give birth in order to produce milk. As a result, the separation of cow and calf shortly after birth is an integral yet distressing part of modern commercial dairying.

There is an extensive body of research on maternal behaviour in cows that allows us an understanding of the issues surrounding birth and the harmful impact of separating calves before they are naturally weaned. Mother-calf separation is one of the most psychologically damaging aspectsof dairy farming, though it remains largely unknown to the public and is notably absent in the ‘feel good’ marketing of dairy products.

Most dairy calves are forcibly removed from their mothers shortly after birth, causing clear distress to both mother and calf.

In order for a heifer to begin producing milk, it is necessary for her to fall pregnant and give birth to a new calf. As milk production begins to fall quite rapidly after nine months, and two to three months is needed to prepare for the next parturition, she will generally be forced to give birth to a calf every 13 months to ensure that she continues producing a high volume of milk into the next year.

There were about 1.65 million productive dairy cows in milk in the Australian herd in 2012/13. With cows being continually artificially impregnated every 13 months, it is clear that a huge number of calves are born each year to keep the herd milking at a sufficiently high rate.

From the viewpoint of the farmer, and the industry more broadly, each calf is a necessary by-product of milk production.

From the mother cow’s point of view, however, the situation is very different.

Why Separate?

Under natural conditions, calves will generally remain with their mothers until they are gradually weaned at around six to eight months. The longer the cow and calf remain together, the stronger the bond between them.

Under natural conditions, calves will generally remain with their mothers until they are gradually weaned at around six to eight months. The longer the cow and calf remain together, the stronger the bond between them.

The routine practice of separating a calf from his or her mother shortly after birth, however, is usually done to ensure the highest yield of milk is available for sale.

In the past, calves would often be left with their mothers for the first 12 to 24 hours in order for them to consume the first essential to health milk: the colostrum.

It is now common practice and recommended by the dairy industry to separate the mother from her calf within 12 hours of birth, then feed the mother’s extracted colostrum to her calf from a bottle or bucket.

Separation also seeks to address an additional problem that now exists: the possible inability of calves to suckle from their mothers–the udder of the modern dairy cow is so pendulous, her teats are no longer positioned where the calf has been genetically programmed to find them.

While this issue may only affect a small proportion of calves, the reality is that her udder may now be more suited to a milking machine than a newborn calf.

Denial of Maternal Behaviour

Cows are deeply maternal animals, and a review of the literature shows that they will engage in a number of diverse behaviours to ensure the growth and survival of their calves.

In the first seven minutes after birth, if left alone, mothers lick their calves and then intensely groom them for the next 30-40 minutes. This behaviour is strongly instinctive and satisfying for both mother and calf, and one which is considered essential in establishing their bond, as well as encouraging activity in the calf which is likely to have other positive effects such as stimulating breathing, circulation, urination and defecation.

Cows will vocalise immediately after the birth of their calves, with quiet grunting sounds used in combination with licking.

As little as five minutes of contact with a calf immediately after birth may be sufficient for the formation of a strong maternal bond.

The early removal of her calf will deny the cow her natural expression of her maternal and nurturing instincts. While the calf must only suffer the stress of separation once, mother cows are forced to endure repeated pregnancies and separations.

Distress in Mother Cows

Scientific evidence now tells us that dairy cows are affected by the separation process. For days after their separation, a mother can bellow day and night in search of her calf, often returning to the place where the calf was last seen. There have even been instances of mothers escaping and travelling for miles to find their calves on other farms.

Behavioural responses indicating stress include restlessness, sniffing, increased vocalisations and activities that would naturally serve to reunite the cow and calf upon separation. Both behavioural and physiological distress responses become more intense with late separation and when mother cows are able to see and hear their calf. Studies also show a mother cow’s heart rate will increase when they hear a recording of a calf’s call.

When the calf was first removed, she was in acute grief; she stood outside the pen where she had last seen her calf and bellowed for her offspring for hours. She would only move when forced to do so. Even after six weeks, the mother would gaze at the pen where she last saw her calf and sometimes wait momentarily outside the pen. It was almost as if her spirit had been broken and all she could do was to make token gestures to see if her calf would still be there.

– Jeffrey Masson, RSPCA Great Britain.

Distress in Bobby Calves

The natural behaviour of calves is to maintain a strong bond with their mothers, which can last well beyond the point of natural weaning.

The natural behaviour of calves is to maintain a strong bond with their mothers, which can last well beyond the point of natural weaning.

Calves experience distress following maternal separation at approximately 24 hours after birth, showing signs of low mood and negativity following separation.

A study revealed that calves are emotionally impacted by separation, drawing a link with the anxiety experienced by calves following the pain of hot iron disbudding.

Initial signs of mild distress following early separation include increased heart rate and vocalisations. The behavioural responses of calves to separation increase, however, after a stronger maternal bond has formed, with one study showing calves displaying abnormal behaviours, including signs of movement, butting, urination and vocalisation and reduced grooming, lying and eating when separated at 72 hours.

We know that many mammals grieve the loss of their offspring and dairy cows are no different.

Bobby Calves

Every year around 800,000 calves are slaughtered in Australia within the first week of their lives. Labelled ‘bobby calves’ and treated as wastage by the dairy industry, their suffering is a hidden and disturbing truth of modern dairy farming.

Once they are born, calves are divided into two categories: ‘replacement’ calves who will eventually replace the worn out milking cows and ‘non-replacement’, unwanted bobby calves, who are destined for slaughter.

In order to keep milk production high, farmers continually impregnate mother cows. This is despite the possibility that they will give birth to calves that are unsuitable for use as milkers and will inevitably need to be slaughtered soon after birth. These bobby calves are in a very real sense, the ‘waste products’ of the dairy industry.

Dairy calves will continue to be taken from their mothers, endure the stresses of long distance travel, and be prematurely killed, often brutally, in their hundreds of thousands every year.

Around 700,000 calves are transported live for commercial slaughter each year, sold for use in pet food, leather goods, the pharmaceutical industry or to be processed into pink veal for human consumption. The remainder will be slaughtered on-farm at or soon after birth.

Transport

In Australia, bobby calves can be transported at just five days of age. Unlike other countries, Australia does not have a well established industry to process bobby calves, so they are often required to travel long distances to slaughterhouses and saleyards.

Live animal transport can be a severely stressful process for animals, particularly for young calves who have not yet had the time to develop adequate coping mechanisms to respond to the stresses of travel.

Calves often succumb to post-transport respiratory and gastrointestinal infections. Depending on the time of year and location, they may also suffer from either thirst, heat stress or hypothermia.

In Australia, how long bobby calves can be transported are as follows:

- VIC, NSW, SA, QLD: Up to 6 hours for bobby calves less than 5 days old, and up to 12 hours for bobby calves between 5 and 30 days old.

- TAS: Up to 10 hours for all bobby calves.

- WA: Up to 36 hours (with a rest at 24 hours) for bobby calves less than 1 month old traveling with their mother, and up to 36 hours for bobby calves older than 1 month.

Calves are inevitably hungry and thirsty during transport. The science shows that calves will naturally suckle from their mother around five times a day and will likely experience hunger about nine hours after their last feed.

Cows and calves are unlikely to lie down in the first 15 hours of transport due to stress, which is unnatural for newborns.

Bruising and injuries are frequentlyobserved in animals following transport (particularly those travelling long distance) as a result of rough handling, increased aggression from mixing unfamiliar animals, poor vehicular design and vehicular movement.

Studies indicate that transported calves are more likely to die than those that remain on-farm, and that this mortality increases exponentially with the distance travelled. Using a study from 1998 – 2000, it is estimated that approximately 4,500 calves would die en route annually in the current industry, not including sick or injured calves that will die on arrival.

On-Farm Slaughter via Blunt Force Trauma

Calves who are not transported to farms, sale-yards or slaughterhouses are either sold for dairy or beef rearing, or killed on-farm. It is estimated that over 65,740 calves are slaughtered on-farm each year, their carcasses either immediately disposed of or processed at local knackeries.

Alarmingly, blunt force trauma is a routine and lawful method of slaughter for those bobby calves who remain on farms, and it is also the cheapest.

Blunt force trauma involves the delivery of a forceful blow to the skull of a newborn calf with a hammer or blunt instrument.

Manually applied blunt trauma has been found by veterinary experts to be a cruel, imprecise and inhumane method of slaughter that cannot and should not be justified on economic grounds. The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) deems it an unacceptable method of euthanasia for calves because their skulls are too hard to achieve immediate unconsciousness or death.

It is important to reiterate that bobby calves as individuals are of low monetary value which ultimately affects their treatment.

Few legal protections exist to protect unwanted calves on-farm.

Husbandry Practices

Disbudding and Dehorning

Disbudding and dehorning are standard mutilation practices used to remove or stop the growth of horns in livestock. Despite claims to the contrary, all methods of dehorning and disbudding cause chronic and acute pain to calves and adult cows.

Disbudding is the removal of the horn bud (and horn producing cells) before it attaches to a calf’s skull, and is usually performed on calves less than two months of age. Disbudding typically involves the removal of the horn bud with a hot iron scoop or through chemical (caustic) application.

Vigorous and violent escape behaviours displayed during disbudding indicate that cows experience pain and distress.

Dehorning is the process of removing the horn and surrounding tissue of older dairy calves and adult cows after the horns have attached to their skull. This is performed using a variety of tools, including a dehorning knife, hand and electric saws, guillotine shears or scoop dehorners.

Beyond the immediate experiences of stress and pain, dehorning often causes trauma to the cow’s frontal sinuses posing the risk of infection, excessive bleeding and prolonged wound healing.

While the dairy industry recognises that both procedures can be painful to some degree, both dehorning and disbudding can be routinely performed in all Australian jurisdictions without pain relief.

There is a wealth of scientific evidence which shows that all methods of disbudding and dehorning cause distress and pain to the calf and adult cow.

In addition to heat cauterisation methods of disbudding, Australian dairy farmers also have the option of chemical cauterisation, known as ‘caustic disbudding’. This involves the application of an acidic paste to the horn buds of calves to destroy horn-producing cells. Even though it has been argued that the pain may be less severe than hot iron disbudding, chemical cauterisation is known to cause extreme pain, with tissue damage increasing whilst the chemical is active.

Tail Docking

Tail docking involves the amputation of a cow’s tail, usually without pain relief. It can cause acute and chronic pain and the use of a local anaesthetic offers little to no pain relief for cows. While this painful practice is no longer endorsed by the Australian dairy industry, and may soon be prohibited, it is currently legal in many Australian jurisdictions and was performed by 18% of dairy farmers in 2012.

Tail docking was originally practiced to avoid leptospirosis in farm handlers, a disease which can infect humans exposed to animal urine. No scientific evidence exists, however, linking tail docking to the reduction of leptospirosis, with herd vaccination and improved worker hygiene being more effective means of reducing the risk of human infection.

Cows use their tails as an indicator of their mood and for social signalling with other cows in the herd. As such, the removal of the tail limits their social behaviour and impedes their normal activities. Cows will also use their tail to swat flies so, particularly in the warmer Australian climates, tail docking can cause irritation from biting flies and result in the potential use of insecticides and other pest control measures by farmers.

Calving Induction

Calving induction is the use of hormone treatment via injections to unnaturally induce labour in pregnant cows.

Calving induction is the use of hormone treatment via injections to unnaturally induce labour in pregnant cows.

Calving induction can be used by veterinarians to treat overdue cows and hasten calving to address prenatal health concerns.

In the dairy industry, however, induction is commonly used as a tool for herd management to force early births as they run on a regimented schedule.

Keeping to schedule means Australian farmers:

- Ensure that the annual period where pasture is most abundant coincides with the time when all the cows in the herd require the most food. This means that all cows are able to produce the maximum amount of milk possible for the longest possible time.

- Ensure additional on-farm benefits of induced calving which can include higher milk production by inducing late cows early, thereby gaining an extra months’ production from late cows at the start of the season.

While this practice affects only a small percentage of dairy cows, the welfare implications are significant. Many calves are stillborn or die shortly after birth, while, as a result of induction, mother cows are susceptible to dangerous health complications: retained foetal membrane (placenta), weakened immune systems, and risk of infection.

Breeding Technologies

Selective Breeding

Over the past 50 years, the reproductive capability of dairy cows has changed dramatically as the dairy industry has become more focused on breeding for high milk yield. Often the better a cow is at producing high volumes of milk, the more difficulty she may have in naturally conceiving a calf.

Over the past 50 years, the reproductive capability of dairy cows has changed dramatically as the dairy industry has become more focused on breeding for high milk yield. Often the better a cow is at producing high volumes of milk, the more difficulty she may have in naturally conceiving a calf.

Selective breeding is the process of breeding animals for particular genetic traits to produce offspring who also show those characteristics.

The continuous inbreeding of particular genes lowers the genetic diversity of the herd and runs the risk of breeding some genes out of the gene pool altogether.

Studies have shown that the combination of selective breeding narrowly focused on production traits and the intensification of animal production systems have resulted in poor welfare outcomes for cows, with such increases in:

- Genetic disorders,

- Metabolic stress,

- Lameness,

- Mastitis,

- Reduced fertility and longevity.

Artificial Insemination

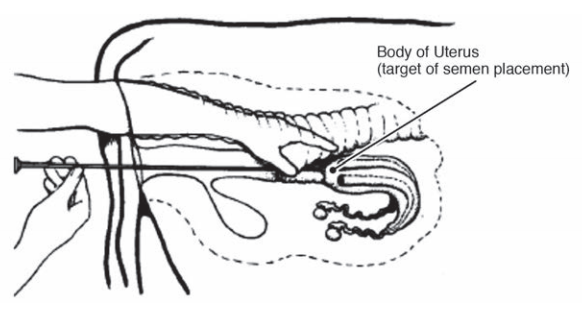

Artificial insemination (AI) is used widely across Australia and is a highly invasive procedure which typically involves a farmer manually inserting semen directly into the uterus of a female cow using their hand and an applicator gun.

AI speeds up the process of selective breeding by offering farmers the opportunity to choose semen from bulls with desirable genetic traits.

Genomics allows AI to be even more accurate and efficient and allows farmers to immediately evaluate the genetic traits of a cow or bull through DNA profiling. Animals who are considered genetically desirable can have their DNA placed on a genomics register from which farmers can purchase semen samples to develop their herds.

Embryo Transfer

Embryo transfer is the process of removing embryos from a donor and placing them into the uterus of a surrogate to establish a pregnancy. The surrogate mother then gives birth to a calf who is genetically unrelated to her.

The purpose of embryo transfer is to speed up the process of selective breeding within a herd, as any female cow can act as surrogate for calves with preferred DNA.

It is important to remember that these breeding technologies have contributed to the massive increase in milk production of the modern dairy cow.

This concentration on milk yield has contributed to a loss of fitness through increased predisposition to infertility, metabolic disorders, mastitis and lameness, all of which cause great distress and suffering to dairy cows on a daily basis.

Injuries and Disease

Lameness

Lameness is a serious issue within the Australian dairy industry, and indeed dairy industries worldwide. Lameness is a structural or functional condition which usually affects a cow’s limbs inhibiting her ability to walk, stand up, lie down or move around. Lameness can be a result of either excessive wear, foot lesions, or infectious disease such as foot rot.

In pasture-based systems like Australia, the causes of lameness may include one or more of the following major risk factors:

- Poor maintenance and design of the tracks which cows use to move around the farm;

- Farm handlers moving cows along the track or yard too quickly;

- Cows spending extended periods of time on hard concrete surfaces;

- Exposure to excessive moisture including standing in manure or on wet floors;

- Nutritional effects;

- Stress;

- Presence of, and exposure to, infectious agents like bacteria and fungus; and

- Genetic factors, such as breeding for high yield milk rather than disease resistance.

“Imagine that you caught all your fingers of both hands in a doorjamb, hard. And then you had to walk on your fingertips. So when you see a cow hesitating to put one foot in front of the other, you can be sure she is feeling excruciating pain.”

Cows are more susceptible to the conditions that cause lameness in the period of calving when the pressure on their bodies is at its peak. Given that dairy cows are repeatedly impregnated throughout their lives, mother cows are constantly under the types of physical stressors which cause lameness.

As a response to pain, cows will lie down as much as possible, may go off their food, lose weight and fertility, not socialise and lose status in the herd. Cows who are unable to lie down because of lameness will stand with arched backs and lowered heads in an attempt to take the weight off their hind limbs.

Critically, herd animals like cows and sheep do not naturally show overt signs of pain because this is an indication of weakness or vulnerability.

Mastitis

Mastitis is a common disease which affects the udders of commercial dairy cows where inflammation of the mammary gland is caused by the invasion of bacteria into the udder via the teat canal. Research shows that even a mild case of mastitis can make daily activities painful and distressing.

Increasing milk demands, forced repeated pregnancies and genetic selection to favour production traits over welfare (such as oversized, pendulous udders) have resulted in mastitis becoming a widespread problem in the dairy industry.

Due to the extraordinary burden of milk production which is placed on the modern dairy cow, including continual calving, infections of the mammary gland are common.

Common symptoms of clinical mastitis include abnormalities in the udder (such as swelling, heat, hardness, redness, or pain) and the milk (such as a watery appearance, flakes of blood, clots, or pus). Other symptoms may include an increase in body temperature, lack of appetite, sunken eyes, diarrhoea and dehydration.

Dairy Australia calculates that more than $150 million is lost to Australian farmers each year through poor udder health, with mastitis being the major cause of this loss.

Live Exports

Australia is one of the few countries to live export dairy heifers and cows overseas as breeder stock. To feed the world’s growing appetite for dairy products, these animals are shipped long distances in stressful conditions to countries with little or no animal welfare protections.

In 2013, Australia live exported around 850,923 cattle overseas, the majority of whom were shipped and slaughtered for their meat. In 2013, Australia exported 79,723 dairy heifers and cows live to foreign markets, a 4% increase on the previous year. The majority of these were Victorian and were predominantly exported to China (61,906), Indonesia (11,069), Thailand (3,595) and Pakistan (1,514).

Australian dairy heifers and cows are especially sought after because of their high value milk production, with the export industry now valued at approximately $172 million.

Shipping Impact

The journey from farm gate to final destination is long and arduous. At sea, these animals are deprived of food and water for long periods and commonly lose weight during the journey. The stress of transportation can suppress their immune system, potentially increase their likelihood of disease, while heat stroke, trauma and respiratory disease are common causes of mortality for animals throughout the live export journey on long haul voyages, although mortalities en route are relatively low.

Typical stocking density of animals on live export boats; no room to move.

Much of the cruelty and welfare concerns inherent in the live animal export trade cannot be legislated away, such as the forced change in diet and environment, heat stress, lengthy loading times and travel times, and the inability of our government to protect animals beyond Australia’s coastline.

The China Story

China is by far the biggest importer of Australian dairy animals as the nation moves to create its own independent and profitable dairy industry. In 2013, China imported 78% of the dairy heifers and cows Australia sent overseas (around 59,235 animals), at a total value of around $125 million.

Chinese milk producers are beginning to adopt the US-style of intensive farming systems where cows live in football-field-size covered sheds, rarely venture outdoors and are milked three times a day on German-made, bovine merry-go-rounds, with automated pumps that measure each cow’s milk flow by the second and send that data to central computers.

The enormous pressure placed on the cow’s immune systems often results in their becoming ‘spent’–or economically unviable–at a very early age.

China Modern Dairy, the country’s largest milk producer, houses up to 20,000 cows within these football-field-size covered sheds. As of 31 December 2013, the Group had 22 farms operating and four under construction, with approximately 186,838 dairy cows in total. The organisation plans to reach 300,000 dairy cows by 2015–that equates to a massive 7,950 cows per shed.

Overseas Farming Conditions

The suffering of breeder animals continues once they reach their destination. The survival rates of those calves born overseas is one of the only useful measures available to gauge the welfare standards of calf-rearing systems in importing countries.

Surveys in Southeast Asia reveal that pre-weaning calf mortality rates of 15-25% are reported as ‘typical’ on many tropical dairy farms (Australia’s pre-weaning mortality rate is 3%), with reports of calf deaths as high as 50%. These figures are a strong indicator of very poor calf management, and other factors such as humidity and temperature, poor housing and hygiene, poorly balanced diet due to quality of available feed, insufficient rumen (cud chewing), poor access to veterinary support and a lack of farm handler skill and knowledge.

Breeder heifers and cows are regularly transported overseas whilst pregnant. These animals are at risk of abortions, dystocia (difficulty giving birth) and becoming moribund due to metabolic problems associated with pregnancy.

The international welfare standards that do exist are generally lower than those that apply to animals in Australia. For instance, the pre-slaughter stunning of cows is not a requirement under the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) standards.

Investigations have exposed cruelty to Australian cows exported overseas. These investigations have routinely shown cruel methods of slaughter, including the use of roping techniques, full inversion boxes and makeshift abattoirs.

Australian cows brutally killed in the Gaza Strip, February-April 2014.

The Commonwealth’s attempts to regulate live animal exports serves only to legalise and legitimise systemic animal cruelty.

Most Australian animals who are exported live are subject to the Exporter Supply Chain Assurance System (ESCAS), a series of regulations introduced in the wake of the 2011 Indonesia live export cruelty exposé. However, breeder animals are exempt from ESCAS, so exported dairy cows are not afforded even the most basic protections once they have disembarked in destination countries.

If the Government is not capable of ensuring that these animals can be treated humanely, it should not be legal to export them overseas. Only a ban on live animal exports will put an end to the cruelty of this trade–a position that is shared by the vast majority of the Australian public including a number of Australian politicians.

Changing Industry and Attitude

Role of Consumers

Growing consumer demand for cheap dairy products, especially within Australia, has exacerbated pressures on both dairy farmers and dairy cows.

Growing consumer demand for cheap dairy products, especially within Australia, has exacerbated pressures on both dairy farmers and dairy cows.

Colloquially referred to as the ‘$1 Milk Wars’, this price is reflective of a 2011 major marketing strategy by Australia’s two largest supermarket chains, Coles and Woolworths, to cut the cost of milk to A$1 per litre for consumers.

The impact of increasing consumer demand for cheap milk forced dairy farmers to maximise their productive output while reducing their overall operative costs, and the implications of high production dairying on the modern dairy cow are immense.

The true cost of cheap milk, therefore, is ultimately paid by the dairy cow.

Many Australians are unaware of the conditions in which dairy animals live. This situation is rapidly changing, but more needs to be done to bring the realities of dairy farming to the mainstream.

Need for Reform

It is clear that law reform is needed to better protect the dairy cow and her calf. At the time of writing, the draft Cattle Standards and Guidelines, which is intended to replace the existing Cattle Code, is in its final stage of review. Unfortunately, the latest draft fails to adequately address the majority of our welfare concerns.

Within the dairy industry, enforcement efforts are heavily dependent on industry self-auditing and reporting, which focus on food safety and milk quality, as opposed to animal welfare. The current dependence on industry self-reporting is clearly problematic, with industry effectively monitoring and regulating itself.

Animal welfare can never be assured without regular independent monitoring and enforcement.

Conclusion

In shining a light on the daily life of the Australian dairy cow, through a systematic examination of the key welfare issues, it is clear that too frequently, the answer to these questions is ‘no’.

The modern dairy cow commonly suffers from mastitis, lameness, metabolic disorders, mutilation procedures and the inevitability of repeatedly losing her calf. It is also clear that much of her suffering and poor welfare is made worse by the demands placed on her by high-production dairying and the growing consumer expectation for cheap milk.

Reform is needed to address this situation and must take place across different jurisdictions and at different levels of government and society.

As has been the case in other animal industries, consumer action provides the greatest opportunity for improving the lives of dairy cows and their calves. Through the ethical choices of informed consumers, retailers and producers have begun making changes that have dramatically improved the lives of millions of hens and mother pigs that would have otherwise spent their lives in cages or sow stalls. Of course, millions more continue to suffer in factory farms, but consumers have given them a voice and have brought their suffering to mainstream awareness.

In addition to providing information, our aim and our hope is that this Report will spark discussion and debate among farmers, industry bodies, policy makers and consumers. We have shown in the Report that there are kinder ways to produce dairy products and also that there are now many viable alternatives available.

The consumer has enormous power and armed with information, is in a position to make ethical and compassionate choices. We hope that in giving voice to the dairy cow, and her calf, the informed consumer will be in a better position to make those choices.